A young man named Rob hears a voice in his earbuds. It belongs to his favourite true-crime podcast host, Matthias. Like all good podcast hosts, Matthias takes pride in addressing his audience as individuals, developing a rapport and a trustworthy intimacy. So when Matthias tells Rob to murder women, Rob obeys.

This isn’t a true story but the plot of the 2017 audio drama Monster’s Game. But like all good fiction, this horror story has a basis in reality: our contemporary, sometimes ghoulish fascination with true-crime podcasts. The 19th century had a similar macabre popular fascination, the penny dreadful.

In the 19th century, people enjoyed a tale of murder and woe as much as we do now. From their complicated relationship with journalism to their love of sensationalism, the two forms have a lot in common.

Fake murders and violent crimes

Penny dreadfuls arose in Britain the 1830s due to a growing number of readers and improved printing technology. The penny post and railway distribution also played a part. While literacy levels are hard to establish, by the 1870s, most of the working class could read well enough to read a newspaper.

This explosion of crime literature gave a bewildered populace the erroneous impression that violent crime (especially murder) was increasing, as historian Christopher A Casey notes. This led to many believing that cities had never been more dangerous to live in and had startling implications for criminal justice in Britain. For instance, capital punishment, which had almost disappeared in the 1840s and 1850s, was reinstated in 1863.

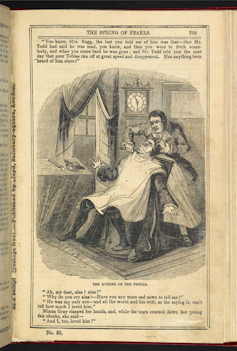

With so much printed material on violent crime, it’s perhaps not surprising that the penny bloods (renamed penny dreadfuls in the 1860s) were so incredibly popular. The name change is thought to have happened because of the shift from tales of highwaymen and Gothic adventure to true crime, especially murder. And if there weren’t enough real crimes, the writers invented them, as with, most famously The String of Pearls, which was the first story to introduce the demon barber of Fleet Street, Sweeney Todd.

Serialised, short, printed on flimsy paper, cheap and luridly illustrated, penny dreadfuls were issued weekly to a large eager audience. There were a 100 publishers,) of penny-fiction and magazines between 1830 and 1850 and by the 1880s there were 15 periodicals competing simultaneously.

Casey links the newspaper era that parallels the rise of the penny dreadful with the gestation of the 19th century idea of “new journalism”. Coined by cultural critic, the term refers to a wide range of changes in British newspaper and magazine content, which sought to make print culture more accessible to working class and female readers. This included a shift away from political news coverage to wider reporting on crime, which focused on the journalist putting themselves in the story and often shaping it.

While this idea of “new journalism” arose in the 19th century, it has links with our current era. Observing the wide range of subjects for podcasts, the journalism academic Mia Lindgren has discerned how investigative journalism podcasts (a genre identified with true crime) quickly became very popular. This swift rise is similar to that of penny bloods.

Moral outrage

The true crime genre, of course, predates podcasts, but its recent renaissance is, in part, due to award-winning productions like Serial. In 2019, 22 of the top 100 podcasts on iTunes were true crime.

Like penny dreadfuls, these podcasts are about real murder and mayhem and naturally blur the line between news and entertainment.

Like penny dreadfuls, true crime podcasts tend to be serialised, short, of variable quality and drop weekly or bi-weekly. They may not have the lurid illustrations associated with penny dreadfuls, but the supplementary visual assets on their websites are arguably just as visually arresting — and necessary to the format. Readers of penny dreadfuls wanted to see an illustration of what the murderers and victims looked like; modern podcast listeners also enjoy having their aurally stimulated storytelling supplemented with colourful podcast logos, images and videos of the podcast hosts, and pictorial evidence of crimes.

Penny dreadfuls were developed to cater to a specific youth audience. They generated a moral panic and were held responsible for inspiring real acts of violence as juveniles exposed to such “trash” were thought to be morally corrupted. For example, in 1895, Robert and Nattie Coombes, aged 13 and 12, admitted to stabbing their mother to death. The police discovered a collection of penny dreadfuls in the house, which the coroner argued had led the boys to commit the heinous act.

True crime podcasts haven’t been accused of corrupting the young and contributing to juvenile delinquency (yet) but the consequences for real people involved in real investigations have been felt. One example comes from Serial. As the podcast’s investigations threw doubt onto whether Adnan Syed was responsible for the murder of his high school girlfriend, a crime for which he had been jailed, avid listeners began searching and stalking Jay, the person Adnan says is responsible for the murder.

Podcasts seem to be, at worst, tolerated as escapist entertainment, and at best, able to influence the criminal justice system — in a more socially progressive way than crime reporting did in the 19th century. The charity the Innocence Project has seen increased donations as a result of podcasts and listeners appear in court to support defendants. Judges even cite podcasts as reasons for changing their decisions on defendants’ motions for post-conviction relief.

The economic historian John Springhall noted that “often-reprinted serials about low-life crime and mystery … would have held a vicarious appeal for young metropolitan readers seeking a romantic escape from uneventful daily lives”. True crime podcasts have also been a welcome escape from the monotony of life in lockdown during the pandemic. Investigative podcasts like The Washington Post’s Canary, a seven-part series about women who refused to stay silent about sexual assault, and CounterClock, which investigates two unsolved murders, have made it on to lists of the best podcasts for 2020. Both podcasts and penny bloods satisfy a lurid fascination in all that is dark and violent. A fascination that is sure to push the true crime genre to even greater heights in years to come.